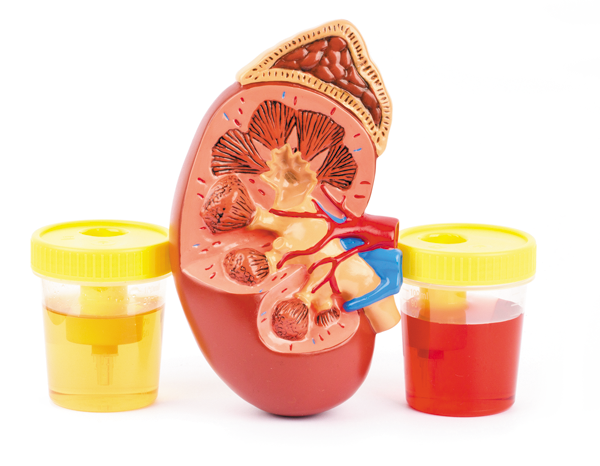

ematuria can be one of two kinds. Blood that can be seen by the naked eye, called gross hematuria, and blood that cannot be seen by the naked eye, called microscopic hematuria. Either condition can occur with or without pain. Gross hematuria can be very surprising for a patient when pain is not present, and can cause much anxiety. Microscopic hematuria that has not been evaluated can also be a quandary for both the patient and physician.

When blood is found in the urine, it represents a disruption of normal human physiology.

The kidneys act like a filter and should keep good large things like red blood cells in the blood and excrete excess fluids and food break down waste products like creatinine and urea.

Blood in the urine can arise from a multitude of possible sources. These include:

- Infection: Bladder, kidney, and prostate. Viral, Post- streptococcal, E-coli Hemolytic Uremia.

- Stones: Kidney, ureter, bladder.

- Prostate: Infection, benign prostatic hypertrophy, cancer

- Cancer: Kidney, bladder, prostate.

- Inflammation: Post catheterization, interstitial cystitis.

- Kidney disease: Glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, auto- immune nephritis.

- Inherited genetic disorders: Sickle cell anemia, Alport Syndrome.

- Medications: Blood thinners, cholesterol medication, anti-cancer drugs, penicillin.

- Traumatic injury: Strenuous exercise or physical trauma.

Some of these sources can be immediately life threatening, some have an intermediate time frame risk, like kidney or bladder cancer that can spread, and other sources, like blood from running a marathon, can be self limiting.

Any case of gross hematuria warrants evaluation, and microscopic hematuria that has a persistent pattern warrants evaluation and should not be dismissed by the patient or practitioner. Medical workup depends on history of illness, physical exam, and likely causes. Blood work

can ensure proper kidney function, rule out kidney disease and inherited disorders, and help further evaluate urologic conditions like PSA testing for the prostate.

Microscopic hematuria that occurs on urinalysis without other evidence of infection should not be simply written off as infection. A urine culture and follow-up urinalysis can help avoid treating a serious underlying illness with antibiotics.

Important tests are typically performed to evaluate painless hematuria after an in-office urinalysis confirms blood. These include cystoscopy and CT urography. If a kidney stone is probable, a non-contrasted CT is performed.

Cystoscopy is similar to colonoscopy in that a small cam- era is used to visualize the internal structures of the lower urinary system, namely the urethra, sphincter muscular which allows for bladder control, the prostate fossa in males, and the bladder. If a clear source of the hematuria is found, like a bladder tumor, it may be deemed reasonable not to perform additional tests and expose the patient to unneeded radiation and cost.

CT urography is a “CAT scan” that images the urinary system and is performed using IV contrast in which 3 phases of pictures are taken. Phase 1, before contrast is given, is sensitive for kidney stones. Phase 2, as the contrast makes its way through the blood and kidneys, is sensitive for picking up on vascular and kidney abnormalities, and phase 3 after the contrast has made its way through the urinary system is sensitive to evaluate for ureter obstruction and large bladder tumors.

Blood work, cystoscopy, and CT urography can help rule out a large number of concerning causes of hematuria. Talk to your doctor today if you have had an episode of gross hematuria, or if you have a pattern of microscopic hematuria on urinalysis, and make an informed decision with their help about how to properly evaluate it.